Today I want to celebrate niche tooling that makes life more comfortable on the computer. For context, I like to work with computers from the keyboard, minimizing use of the mouse. But this is often difficult to do consistently, especially when everything is a web app, a world known to be mouse-focused. Let me tell you about the fantastic Firefox extensions Vimium, and Edit With Emacs, both of which make the keyboard life more pleasant.

…Jiby's toolbox

Jb Doyon’s personal website

Recent posts

I’ve been thinking a lot about risk registers recently. I feel like people don’t know enough about them, or reject them on principle for being “more process”.

I’ve worked in projects where the process was heavy, and like many, I very much didn’t like it then. But since moving to more “agile” environments, I’ve repeatedly been missing the structured aspects of writing things down, and wished for more rigour, more … process?

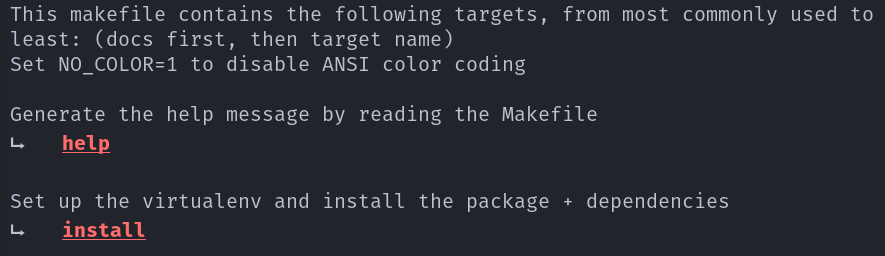

…I’ve written in the past about using Makefiles for build automation and documentation. But sometimes I wish to provide help to users, that doesn’t require being a Makefiles expert to read!

Let’s explore how we can teach users our build system by turning

the project’s Makefile (and awk) into a cheap documentation-as-code tool.

What it looks like

make help

Figure 1: Result of asking for help

…The packaging workflow of Python has historically been a bit messy, starting

with pip being just good enough, and virtualenvs being a great idea but a

bit unwieldy. Installation was difficult, and tools like anaconda filled the

gaps.

Lately, there’s been renaissance of package tooling in Python thanks to other languages innovating in the area, inspiring and pollinating the ecosystem, improving the comfort of development.

I want to present here the tools that I use to work with Python, usually latest iterations on well known concepts, to show that Python can be both fun to play with, and safe enough if we use modern tools.

…In the software world, tickets (as implemented in Jira, etc) often have a bad reputation, and I think it’s undeserved, once we reframe what, or who tickets are for.

In this article I want to revisit the purpose of tickets, usually “tickets for project management”, explore an alternative viewpoint of “tickets as engineering records”, and highlight how tickets should be useable as asynchronous alternative to (synchronous) communication.

Tickets as project management

Under this fairly common viewpoint, tickets are a project manager’s tool, almost inflicted upon devs, likely in an attempt to punish them for their arcane powers over machine, who knows (I’m of course exaggerating on purpose).

…In programming, there are patterns everywhere: patterns of building code, patterns for organising components, even patterns for how to test things. A whole industry is looking for patterns to solve all their problems.

But amongst them all, there’s one pattern I whole-heartedly love, it’s the Early Exit. In this short and sweet post, I want to declare my undying love to the Early Exit, sharing my excitement.

From If+else to ladders and conditionals hell

Functions routinely need to check some edge case isn’t hit, usually with more edge cases than actual routine happy-path code lines.

…Since my earliest university days, I’ve spent a lot of time trying to get better at computers, immersing myself in the world of Linux, and generally improving my software development skills.

One of the aspects that was the most helpful to help me grow was attempting to replicate my normal dev workflow, but with less: Learn to operate on Linux not Windows, then learn to do dev via on the terminal instead of GUIs, and eventually learn to do the same but offline, without any network calls.

…Every now and then, at work, I find myself discussing git worfklows, commit messages, branching, releasing, versioning, changelogs etc. Since my opinion has remained fairly consistent for the past few years, I found myself repeating the same points a lot, so I wrote it down. This page is the resulting compilation of my opinions on the software development lifecycle (SDLC), without workplace-specific tangeants.

The article is broken down into ideas + recommendations, with recommendations in bold. Obviously, this workflow isn’t applicable to everyone (sorry, Google! This isn’t a free consultation!) as different teams have needs that should get dealt with differently.

…The most boring part of setting up a new code project is typing the boilerplate: it’s easy to forget bits, so we just copy the last project’s folder and “file the serial numbers off” on the project name.

Copy-pasta-driven project setup is not great though, as it’s too easy to forget replacing values in obscure files, or misunderstand why project is set up that way in the first place, leading to nasty surprises down the line.

…Last Friday, I performed a presentation to my colleagues about Makefiles, and I want to share it to the public.

Of note, this presentation is setting aside what people usually know of Makefiles (autoconf-generated blobs, opaque to any inspection because machine-created), and instead I introduce the concept of file transformation as a graph, then teach Makefiles basics (using SQL commands as an example). We then move on to my plea for simple Makefiles, and their potential for both documentation (explain what your codebase commands are, to the juniors), and as lightweight automation (avoid typing long boring commands).

…